In 1977, Jeanne’s German nationalist ex-husband, Klaus, tells her he’s gotten a new job and wants to take their three-year-old daughter and six-year-old son away for a long weekend to celebrate. Jeanne relents. But Klaus never returns and instead sends Jeanne a letter, delivered by a mutual friend, in which he declares that he has fled to Germany and she will never see him, or her children, again.

The next four months are filled with agony, despair, and anger as Jeanne seeks legal support but quickly learns that federal parental kidnapping laws will offer her little help. She reflects on her tumultuous ten-year marriage to Klaus and the unsettling events that followed their divorce. A product of the patriarchal culture of the 1950s, Jeanne’s nice-girl mentality is being tested and reshaped by the feminist movement of the 1970s, and she finds that the kidnapping ultimately becomes a doorway to unexpected strength.

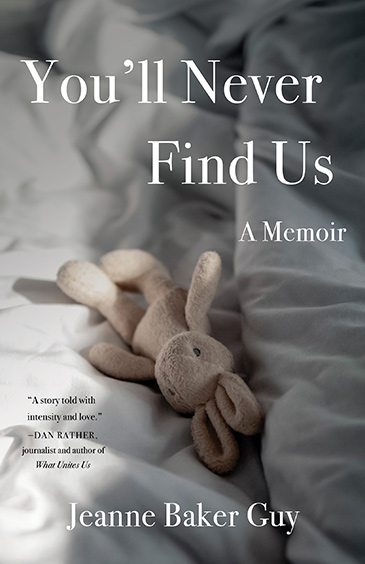

You’ll Never Find Us is the story of a young mother coming into her own power, regardless of past mistakes, bad judgment, and fears; the story of a woman who realizes she must tap into her newfound resilience and courage to find her stolen children—and steal them back.

What They’re Saying

Excerpt

Chapter Thirty-Four

Manthey v. Manthey

1976–1977, Indianapolis, Indiana

We would split everything: the dishes, the silverware, the children. Klaus insisted on no attorney involvement, so we met and laboriously went through item by item, every detail, every stick of furniture. My mantra: Be nice, be fair, and he’ll let you go.

As I sat in my car with a severe headache after forfeiting my plans, my thoughts spun in two different directions. I could hear, but I’m their mother! Children go with the mother—thoughts contradicted by is that fair to their father? The one you betrayed? The one who doesn’t want the divorce? The one who is a “good” father?

I started the engine and backed out of the driveway, my heart hurting worse than my head. When I got home, I looked at my reflection in the bathroom mirror and exhaustion and fear looked back at me—I feared the fight; I feared his anger, and most of all, I feared losing.

I would learn years later of Gloria Steinem’s coining of the term “female impersonator,” referring to our male-dominated society’s socialization of young girls. Men determine what is feminine and girls, at age twelve or thirteen, wanting approval, change their behavior to suit the male rather than developing their own definition of what being a female means.

I had learned early on to play the role of the pleaser, which came with its own internal dialogue of self-criticism. What I had trouble learning is that if you’re always trying to be what someone else wants you to be, it’s never enough. Never enough, the internal critics whispered—not smart enough, not good enough. The charges were a dissonant chorus of voices in my head as I tried to please my way through life. And here I was, wending my way through a divorce, wanting to stand my ground, and those voices were still dictating my decisions.

Jeanne Baker Guy | @JeanneBakerGuy